Teaching Shakespeare: "Macbeth," William Shakespeare

Dear Teacher Colleague:

Part of a year-long High school course in British Literature. In the literature “plan” of a suburban college bound sequence, the students had studied, “Romeo and Juliet” during Freshman Year, “Hamlet” during Sophomore year, and “Macbeth” during Junior Year—so they had been immersed in studying Shakespeare as a required part of their English Language Arts study.

When the Denver Center for Performing Arts housed a professional touring group, the Center offered a matinee performance for Denver Public Schools. We took most of our Junior and Senior High students downtown, and many described the event as a highlight of their four high school years. The students were enthralled with the play—experiencing a “treat” of Shakespeare, and this play was not of the four-year offered curriculum in this school.

So my suspicions were confirmed. I thought it was better to “enjoy,” rather than “study.” I know that was original intention of William Shakespeare, who needed “butts in the seat,” for his play to be successful selling tickets to Londoners who wanted to be entertained.

So how were they entertained?

Scotland was a mysterious country to England. They were ruled by English Kings whom they hated. They sainted their revolutionary rebels (Braveheart) with the underdog story. The Scots were multilingual and they thought that the English were cruel, interested in only exploiting Scot men and destroying their families with high taxes and convenient estates that operated as English Plantations, feeding the folks back home. And so, as underdogs, their stories were filled with love, struggle, frequent disasters and violence permeated their history.

When an Englishman came to see “Macbeth,” they came for the intrigue already woven into their misconceptions about Scotland—so they were surprised when this great soldier, who had been handsomely rewarded with a class promotion, took the advice of witches by murdering his way to the throne. Macbeth, urged by his wife, murdered the good king Duncan in his sleep, and then wiped out any enemy who MIGHT have been a threat to his throne. In other words, there would be no “Game of Thrones” without “Macbeth.”

When a good man turns evil, few men and women can only imagine the shaky processes they invoked to reach their goals. Few of these men and women can only imagine their misdeeds leading to their accomplishments. Shakespeare gives us a unique opportunity to get inside of a madman, sympathized with this murderer, and then see the man exposed. Macbeth and his wife took advantage of the Witches’ prophecies and shortened the process for a minor lord to become a major king. The Witches also set up his downfall—and we discover that along with the culprit, Macbeth, himself.

Usually, when a story ends with the hero-turned-villain Macbeth’s beheading, we feel sorry for the main character. When Lady Macbeth dies, Macbeth has no remorse—he says she picked a bad day to die. When the audience sees Macbeth beheaded, we collectively sigh, and stay silent. Not a tear is shed for the dead king.

Enjoy “Macbeth.” Thank you, Shakespeare.

67 pages; 13,238 words, visuals

Share

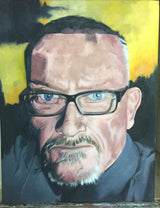

Mr. Brovsky's Vault

To thine own self. be true.

Mr. Brovsky's Vault is filled with Secondary (10-12) Lesson plans for year-long and semester classes in the Humanities.