Modern Politics:RULES FOR RADICALS, Saul Alinsky

Published: 1971; 226 pages

Dialectic Journal/Lesson Plans: 39 pages; 155,455 words; some visuals

“This country's leading hell-raiser" (The Nation) shares his impassioned counsel to young radicals on how to effect constructive social change and know “the difference between being a realistic radical and being a rhetorical one.”

First published in 1971 and written in the midst of radical political developments whose direction Alinsky was one of the first to question, this volume exhibits his style at its best. Like Thomas Paine before him, Alinsky was able to combine, both in his person and his writing, the intensity of political engagement with an absolute insistence on rational political discourse and adherence to the American democratic tradition.

On the other side is the older generation, whose members are no less confused. If they are not as vocal or conscious, it may be because they can escape to a past when the world was simpler. They can still cling to the old values in the simple hope that everything will work out somehow, some way. That the younger generation will “straighten out” with the passing of time. Unable to come to grips with the world as it is, they retreat in any confrontation with the younger generation with that infuriating cliché, “when you get older you’ll understand.” One wonders at their reaction if some youngster were to reply, “When you get younger which will never be then you’ll understand, so of course you’ll never understand.” Those of the older generation who claim a desire to understand say, “When I talk to my kids or their friends I’ll say to them, ‘Look, I believe what you have to tell me is important and I respect it. You call me a square and say that ‘I’m not with it’ or ‘I don’t know where it’s at’ or ‘I don’t know where the scene is’ and all of the rest of the words you use. Well, I’m going to agree with you. So suppose you tell me. What do you want? What do you mean when you say ‘I want to do my thing.’ What the hell is your thing? You say you want a better world. Like what? And don’t tell me a world of peace and love and all the rest of that stuff because people are people, as you will find out when you get older—I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to say anything about ‘when you get older.’ I really do respect what you have to say. Now why don’t you answer me? Do you know what you want? Do you know what you’re talking about? Why can’t we get together?

And that is what we call the generation gap.

What the present generation wants is what all generations have always wanted—a meaning, a sense of what the world and life are—a chance to strive for some sort of order.

If the young were now writing our Declaration of Independence they would begin, “When in the course of inhuman events …” and their bill of particulars would range from Vietnam to our black, Chicano, and Puerto Rican ghettos, to the migrant workers, to Appalachia, to the hate, ignorance, disease, and starvation in the world. Such a bill of particulars would emphasize the absurdity of human affairs and the forlornness and emptiness, the fearful loneliness that comes from not knowing if there is any meaning to our lives.

Share

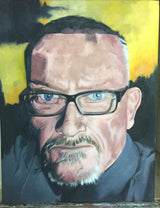

Mr. Brovsky's Vault

To thine own self. be true.

Mr. Brovsky's Vault is filled with Secondary (10-12) Lesson plans for year-long and semester classes in the Humanities.